In this chapter, the nature of human decisions is going to be explored in the context of marketing as well as how emotions influence the decisions consumers make, the human hidden desires and its links with brands. It will also illustrate how former ways of consumer persuasion are relevant to current markets.

Bernays (1928) thought that human beings are rarely aware of what motivates their actions. He claimed that consumers believe they buy a car because they have concluded that is the best choice after a careful study of technical features from different models. The real reason might be the social environment is pushing that person to buy a certain car. "Many of man's thoughts and actions are compensatory substitutes for desires which have been obliged to suppress" (Bernays, 1928. P. 74). A consumer might not necessarily desire something for its intrinsic worth or usefulness, but because of its meaning. A person might really want a car because it is a symbol of social position, an evidence of success. As Packard (1957) puts it, customers buy a promise. Cosmetics sell hope, not lanolin. Oranges sell vitality. Cars sell prestige. One cannot assume that people know what they want or will tell the truth about it even if they do. Packard (1957) assures that people do not seem to be reasonable in their decisions, but this does not mean they do not have a purpose. Their behaviour makes sense in terms of their goals, needs, and motives. In addition to this, Bernays (1928) said that in order to attract customers, a company needs to understand not only their own business but also the structure, personality, and prejudices of their target audience. DuPont's investigators (1945-1954) found out that many people do not make a list of the things they need to buy in the store, which means that shoppers buy on impulse. James Vicary (quoted in Packard, 1957, p.112) suspected that consumers might be under pressure when confronted with so many different choices that they were forced to quickly decide what to purchase.

Olins (2003) explains that a product can connect with the audience using emotional appeals to encourage people to spend money. The key issue, Olins (2003, p. 11) points out, "it is how and where and in what cause it [emotional appeal] is used that is truly significant". Jannson-Boyd (2010) clarifies that it is important to find a mid-point in arousal, not too high or too low, where the audience can have a higher level of attention to stimulate visual selective attention. Humans explore environments mainly visually and there are several theories of what they normally focus on depending on their culture, language (if they write from left to right or the other way around) and so on. Although, Jannson-Boyd (2010) assures that there is not a consistent pattern of how humans conduct a visual search. Ries and Trout (2001, p.19), whose theories about positioning are relevant later on this text, argues "positioning is an organised system for finding a window in the mind. It is based on the concept that communication can only take place at the right time and under the right circumstances".

Olins (2003) claims that it is a fact that people like brands. If not, they would not buy them. There is a flaw in this statement because consumers have to buy certain products out of need. Brands compete with each other when two or more meet the same basic function.

To understand how brands work it is important to understand what motivates human beings. Abraham Maslow (quoted in Lusensky, 2010, p.35-36) claimed that we all aspire to reach the top of his pyramid, either consciously or unconsciously. For example, 'esteem needs' lack of importance when 'safety needs' are not covered.

The lower part of the pyramid represent the basic needs our modern, convenient and relatively safe society. After fulfilling those, we look for something more. Freud (1923), on the other hand, in his second theory about the structure of the physic apparatus, distinguishes three fundamental instances. The 'Id', formed by the conscious and unconscious, is the psychic expression of drives and desires. It is in conflict with the 'Ego' and 'Super-Ego'. The 'Ego' is the acting psychic instance and is the mediator between the other two. It tries to conciliate the normative and punitive exigences of the 'Super-Ego' as well as the demands of the 'Id' to satisfy unconscious desires. Its function is to achieve the greatest degree of pleasure in the limits of reality. The 'Super-ego' is the judge of the Ego and constitutes the internalisation of the norms, rules and parental prohibitions. The specific functions of each entity are not always clear and they are interwoven in many levels and personality is constituted by this model of diverse forces in inevitable conflict. In this model, things like aesthetic needs are the result of our unconsciousness trying to satisfy the Id. The Id can be equally unsatisfied, and the deprivation of biological and physiological needs can cause a person to accomplish cognitive needs to satisfy the Id.

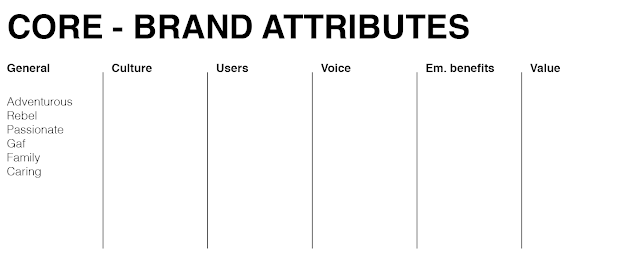

These models can be applied to marketing strategies. For example, Barbara Kruger uses humour to bring forward unconscious and controversial messages such as 'I shop therefore I am' or 'Buy me, I will change your life' to create a comic, controversial and self-aware environment. Riezebos (2003) says the first choice taken in brand values is the aspiration level of the brand. There are three aspiration levels: the need-driven (related to material and biological consumer needs), the outer-directed (consumers' relational needs) and the inner-directed level (need for self-actualisation). "The choice for an aspiration level can be made by taking three factors into account: the characteristics of the product, the characteristics of the organisation and the choices made by competitors" (Riezebos, 2003, p.61). It is important that the strategy avoids creating conflicts or contradicted messages between the aspiration level of a company. Riezebos (2003) points out that the ideal scenario would be to first choose one or two aspiration levels: one that describes the needs on which the other is focusing in greater detail. Then, Riezebos (2003, p.61) specifies "a maximum of three values may be selected within the aspiration level(s) chosen". In the following table, each aspiration level has specific values.

Customers choose brands to tell others who they are and what they believe in. Consuming is a modern way of unconscious expression. In opposition to what Packard (1957) said about controlling customers decisions, marketing does not have an entire control over the brand, customers do. Its power comes from a mixture of performance and what it stands for. If customers find certain harmony in this mixture, they feel it adds an extra meaning to their identities. Lusensky (2010) puts it simpler: brands establish relationships with customers in a human way, so brands are treated like individuals with their own set of values and beliefs. If a personality can be designed for a business, it means that a business can be personified. Human personality traits are associated with a brand, and sometimes, real persons are utilised to represent a brand. For example, Richard Branson with Virgin. Aaker, J (1997) claims that these traits can be associated indirectly through other features like name, symbol, style, price or distribution channel.

Riezebos (2003) links these ideas with design, explaining that the identity must visualise material brand values and an immaterial experience world using visual codes for recognition. These codes can be kept or broken. Marketers need to understand the communication codes in particular cultures to be in control of the meaning. Unspoken rules and conventions that structure sign systems and meanings, Lawes (2002) says. When a personality has to be faithfully conveyed across different cultures, it is important to consider the five factors of brand personality: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. Brand personality offers a way for personal expression by the consumer based on metaphors, symbols, emotional benefits and self-expressive benefits. But what counts the most in communication, Ries and Trout (2001) say, it is receptivity. When two individuals fall in love with each other it is because they are both receptive to that idea. One of the main objectives in advertising is to heighten expectations about a product or service and make consumers believe it will perform the expected miracles. In a talk in 1956 in Philadelphia, Pierre Marineau (quoted in Pike, 2015, p. 27) said that advertising is no longer what it was once: a presentation of the merits of a product. The intention is to create an ideal situation where the customer falls in love with the product that is being advertised. To create this illusion, Marineau said the first task is to create a differentiation in the mind of the consumer, an individualisation from the rest.

Ries and Trout (2001) explain different strategies to be heard in a market where every year there is more to be said than what is received. Positioning help marketers to overcome this, but it is not something that can be done to a product. As explained before, it is the mind of the consumer what can be altered to position a product. Ries and Trout (2001) explain that an oversimplified message is the most effective approach to take in an over-communicated society. Olins (2003) agrees and adds that a product must be differentiated and designed to be in a specific way to appeal to a specific market. Names, typefaces, colours or even music and smells derive from emotional power. There are hundreds of similar products in a very competitive market, all fighting each other to get customers attention. Design has the power in making this differentiation through emotions. It is a matter of choosing what is really important in that message for the best chance to get it through. When a company is second in a market, Ries and Trout (2001) explain that there is an opportunity to take the 'uncola' position. This is due to the strategy that 7-Up once carried out, linking their product with something that already existed in the mind of the consumer as an alternative to it. Conventional logic says that the concept can be found in a brand or its product, but this does not work when trying to find a unique position. It is the consumer's mind that creates it. The 'uncola' is not inside a 7-Up can, it is in the drinker's memory. 7-up took into account the position of their competitors.

This is only one example of many different strategies each position requires. These strategies that use existing businesses are directly related to how the signifier and the signified work for semiotic analysis. The signifier (for example, a brand name) does not have a meaning on its own. The meaning is acquired through associations with other pre-existing meanings until it stands on its own. The signifier is a statement of a fact. The signified is a connotative communication that generates associations, feel and overtones. It can be anything that can be linked with the signifier (Rosenbaum-Elliott et al., 2007). In 1982, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida (quoted in Chapman, 2005, p.12) analysed this and explained that meaning cannot be found in the signifier itself. It can only exist in relation to other things. There is little conscious access to this matrix, but it is everywhere in the human world. The absolute identity does not exist because these concepts are co-dependent. This matrix cannot exist without society, so it is a mirror individuals use to assess their own hierarchical position. Material possessions are deployed as signifiers of status. They allow consumers to cast a desired role. Humans consume meaning, not matter. Objects simply provide the canvas for these connotations for the user. These reflections help individuals to construct their own identity and shape their future. As Olins (2003) puts i

t, markets are very competitive, and rational choice is now an oddity. Brands are there for clarity, status, membership and everything else that helps consumers to define themselves. Claiming that a company is better than its competitors, is not re-positioning. It is comparative advertising and its psychological effectiveness is flawed, since what the consumer easily detects is: "If your brand is so good, how come it is not the leader?" (Ries and Trout, 2001). Olins (2003) defends the same concept and says that rejecting conventions that surround a business is sometimes the best idea. Companies should challenge the existing associations. Sinek (2010) explains that Apple has done exactly this with their computers. They have sold their vision of an ideal world instead of focusing on how the look of their products. For years, cars were becoming better looking and more streamlined, until the Volkswagen Beetle got in the market and challenged the canons of car manufacturing. The conventional way to advertise this car would have been to maximise the strengths and minimise the weaknesses, but they stated their position very clearly: 'think small'. Two simple words stated Volkswagen position and challenged consumer's assumption that bigger is not a synonym of better.

Olins (2003) explains that there are four vectors by which a brand manifests itself: product, environment, communication, and behaviour. In other words: the what, where and how of a company. Brands are usually a mix of these four vectors, and those based on products function are doing right, but that function must be supported by the ergonomics and aesthetics of the design. On the other hand, if the product is not right, the design cannot make it work. People choose hotels based on what they feel like, their facilities and location. These three are all environmental factors. Coca-Cola, for example, is a communication-driven brand, specifically in advertising. Its packaging, materials, events and so on are designed to arouse a very specific set of emotions. These emotions are what makes this product be seen through its communication. Airlines are an example of behaviourally led brands. Customers judge them based on the service and not in the time it took for them to get from point A to point B.

In conclusion, there is not an exact way to persuade consumers to make a certain decision. Designers and marketers can influence those decisions, but there is no guarantee of success as many other aspects fall out of control. Brands are vulnerable to trends, the use consumers make of a brand and also to themselves, as bad management can be self-destructive. However, the right influence of emotions over a long period of time following a strong strategy can humanise brands by giving them personality. This personality is based on a set of assets that are easier to identify and remember for the consumers.